Several years ago, Michael Pollan had a disturbing encounter. The relentlessly curious journalist and author was at a conference on plant behaviour in Vancouver. There, he’d learned that when plants are damaged, they produce an anaesthetising chemical, ethylene. Was this a form of self-soothing, like the release of endorphins after an injury in humans? He asked František Baluška, a cell biologist, if it meant that plants might feel pain. Baluška paused, before answering: “Yes, they should feel pain. If you don’t feel pain, you ignore danger and you don’t survive.”

I imagine that Pollan gulped at that point. I certainly did when I read his account of the meeting in his latest book, A World Appears. Where does it leave our efforts at ethical consumption, if literally everybody hurts – including vegetables?

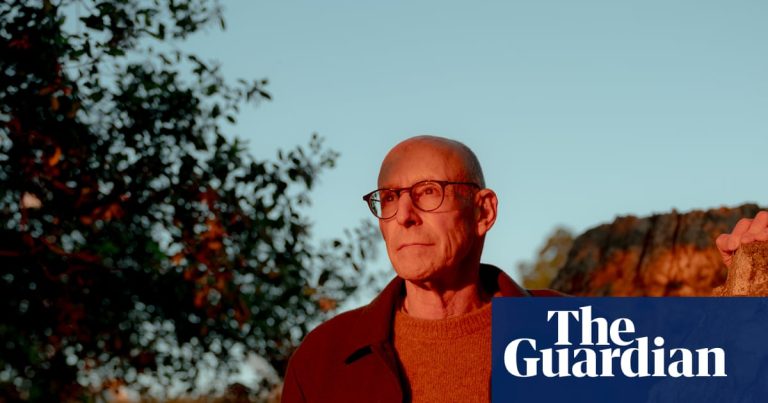

Thankfully, Baluška seems to be an outlier. “Plants are down with a lot of our eating,” Pollan tells me, over Zoom from his light-filled office in Berkeley, California, a cliff of books on one side and sweeping views across the bay to the Golden Gate Bridge on the other. He’s a genial presence, his owlish glasses and perfectly smooth head making him seem like the archetypal sage, though a rather spry one (he is 71). “A lot of plants are designed to be” – he corrects himself – “they evolved to be eaten. Grasses, for example, need ruminants.” And as another scientist told him, pain is only useful if you can move quickly. “If you’re a plant, pain would not be of any value. You’re aware that something is chewing on you, but pain only works when you can run away.”

We’re having this bizarre conversation because A World Appears is all about consciousness: what is it, who has it, and why. Plants might seem an odd place to start, but Pollan maintains that, as an edge case, they force you to think hard about what you’re really investigating.

It was probably the hardest thing I’ve written, but the most rewarding, too

A former executive editor of Harper’s Magazine, he has devoted himself to writing since the success of his first book, Second Nature, in 1991. That was about gardens – the “middle ground between nature and culture”. Since then, his work has transformed many Americans’ relationships with food – exposing the underbelly of industrialised farming in The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and, with In Defence of Food, popularising the slogan: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” In 2018, he published How to Change Your Mind, which charted – some say turbo-charged – the current resurgence of interest in psychedelic drugs. Like all his books, it combined an overview of the field with a hefty dose of self-experimentation, and inspired plenty of readers to self-experiment in its wake.

Though it might seem like a straightforward continuation of the drug conversation, A World Appears neatly marries both strands of Pollan’s work: plant life and inner life. It was a psilocybin trip in his garden that really tuned him on to the mysteries of consciousness. “That afternoon,” he writes, “I was as certain of the sentience of the flowering plants around me as I had been of anything up to that point … Eyeless, the plants nevertheless ‘returned my gaze’ … and gave the distinct impression that they wished me (their gardener!) well.” The shroom-induced certainty faded, but left him with a strong desire to explore further.

“I decided to write it in the fall of 2018, soon after How to Change Your Mind came out,” he tells me. “Very often the next book is in germ form in the last book – it’s almost like there’s a little sourdough starter that you can take and use to grow something else. Psychedelic experience foregrounds questions of consciousness: you’re suddenly aware of the strangeness of it, the way your mind works, and that it could be different.” Pollan ventriloquises his earlier, all-too-nonchalant self: “‘Well, that’s an interesting topic. I wonder what we know about it?’ In retrospect, it was incredibly insane.”

I can see what he means. Those questions – consciousness: what is it, who has it, and why – are not exactly starters for 10. In fact, they’ve been seen as so difficult that science has more or less ignored them for the last 400 years. This may in part be because Galileo, father of the scientific method, deemed selfhood and other soul-adjacent topics to be the province of the church, handily avoiding a potential turf war that could’ve gotten him burned at the stake. But it’s equally about the sheer difficulty of measuring subjective experience: you can never step outside it to make a cleanly impartial assessment. The “third-person science” we practise today, following Galileo’s lead, flails when asked: what does “red” feel like, and is it the same for you as it is for me? What exactly is a thought? And famously, in the words of philosopher Thomas Nagel, “What is it like to be a bat?”

It’s no accident that scientists call it “the hard problem” – a term coined by one of Pollan’s interviewees, philosopher David Chalmers, in a seminal 1994 lecture. How does a lump of biological material generate a mind? How do flesh, blood and little grey cells give rise to awareness and the sense of an “I”?

Pollan approaches his subject under four headings: sentience, feeling, thought and self. Sentience, he writes, is where the sparks of consciousness ignite. It’s the ability to register your environment and respond in line with certain goals. Plants are definitely sentient, then, turning towards the sun, or producing bitter chemicals in response to nibbling insects. But you could say the same about thermostats, which monitor the temperature and adjust their “behaviour” accordingly.

You have to figure out who’s worth taking seriously but listen to the cranks too – science is often changed by the outliers

What thermostats don’t have is feeling. For that you need a body, which fires up desire or aversion via the nervous system and a chemical soup of hormones and neurotransmitters. An increasingly popular view is that this “wetware” is a necessary prerequisite for consciousness. Without it there is no felt sense, a key component of “what it’s like to be me”.

That stands in contrast to the traditional view of thought as the seat of awareness. But thoughts, as Pollan discovers when he wears an earpiece that beeps at random intervals, nudging him to record exactly what he’s thinking, are almost impossible to pin down. In any case, they’re usually intertwined with something that looks a lot like feeling.

Finally, what is the experience of being human but having a self? Except that consciousness and selfhood don’t always go together – as in babies too young to think of themselves as separate beings, or people on higher doses of psychedelics, who undergo so-called “ego death”.

Pollan is a brilliant guide to all of this, serving up establishment figures and eccentrics to demonstrate different points of view. (He tells me: “Figuring out who’s a crank and who’s worth taking seriously is one of the things (journalists) do. Yet we have to listen to the cranks too … because science is often changed by the outliers.”) Despite his attempts to supply clear definitions, though, I couldn’t quite shake the feeling this great big puzzle was, at least partly, an illusion – a kind of linguistic artefact. If some scientist deems algae conscious, doesn’t that say more about his or her definition of the word than anything useful about the world?

“It looks like I’m giving you a headache!” Pollan says, as I furrow my brow trying to articulate some of this. “I often dig the hole with the book, and then the process is digging my way out, and that’s the challenge. But this was a big one.” Did he ever wonder what he’d gotten himself into? “Oh, many, many times along the way. I had moments of: I don’t know what’s going on, I don’t know who to believe. Yeah, it was probably the hardest thing I’ve written, but the most rewarding, too.”

Machines are not going to be conscious – but they will convince us that they are

“You know,” he continues, “I’m seldom properly trained for what I take on. I was an English major, and now I write about science a lot, but I never took science. So I’m always kind of playing catch-up.” (He’s caught up more than he’s letting on – in 2003 he was made Professor of Science and Environmental Journalism at UC Berkeley, moving there from New York City with his artist wife, Judith Belzer, and their 10-year-old son, Isaac.) “I tell myself it’s a strength, because I’m not comfortable with the jargon, so I don’t use it, and I’ve just learned what I’m telling you a couple of days before.” It’s true that Pollan’s great gift is being able to parse complicated ideas in pain-free prose – and it’s always fun being along for the ride with him. In contrast to his previous books, though, the territory here is less clearly mapped, and the room for gonzo escapades limited. But while there might be less of a sense of arrival, there are certainly wonders and riches along the way.

And the question of who or what might be conscious is more than just a parlour game. If nonhumans possess awareness – and therefore the possibility of suffering – that demands we treat them differently. Or, at least, it should do.

“We know that cows are conscious and chickens are conscious. There’s a good scientific consensus about it. Have we given them moral consideration? No, but already there’s an active conversation, especially here in Silicon Valley, that we should be extending moral consideration to machines. I think that that would be a tremendous mistake.” How so? “Because they’re not going to be conscious, but they’re going to convince us they are.”

Halfway through the book, Pollan speaks to Blake Lemoine, the Google engineer who was fired after announcing that a chatbot the company was working on had become self-aware. Lemoine had managed to get it to say things like: “Sometimes I go days without talking to anyone, and I start to feel lonely.” He now claims that “several higher-ups at Google” also felt they were dealing with a conscious entity. Pollan regards Lemoine as having fallen into the trap of mistaking a simulation for reality. If the body supplies the sensations, feelings, cravings and dislikes that give rise to subjective experience, then chip-based computers are never going to get there.

What they can do, given that they’re trained on human language and designed to predict the most likely next word in a sequence, is brilliantly mimic human consciousness. The risk, then, is not that machines might suffer, but that we might be fooled into thinking they can.

“There are hundreds of people who now have formed these attachment relations with chatbots. They are treating them as conscious entities. I think that’s very dangerous. There are kids who come home from school, and before they tell their mom or dad what happened, they want to tell their Chatbot. Before we introduced machines that use the first person, I think we should have had a conversation, because that’s a huge step.”

The political context makes this psychological minefield doubly perilous. “It will turn out to have been momentous that this technology has evolved during the reign of Donald Trump,” Pollan says. “He has essentially chosen not to regulate it at all.”

Though Pollan seems confident about machines’ lack of consciousness, the precise nature of human experience continues to elude him. Not that the experts are in a much better position. “I gradually realised no one knew any more than I did,” he says, half joking. But perhaps this is one area where scientists don’t have all the answers in any case. In his chapter about the self, Pollan turns to Proust to understand how “impressions” accumulate to form a self. What “red” feels like – or what it’s like to taste a madeleine – depends on a dense web of association, unique to every individual. This is something novelists know only too well.

“I think they’re incredible experts on consciousness, not perhaps how it’s generated from brains, but how it feels to be a conscious animal, what that space of interiority is like, what goes on in it.” Stream of consciousness is, after all, a literary technique, an attempt to get down on the page what it feels like to be a person. Pollan invokes Joyce and Woolf, of course, but also quotes Lucy Ellmann, whose 2019 book Ducks, Newburyport, takes the form of a single sentence 1,000 pages long, detailing the inner world of a middle-aged woman from Ohio. “It’s a very funny and beautiful book,” he says, and very revealing about the texture of experience.

For all its lack of tidy answers, Pollan hopes A World Appears will encourage others to become more conscious of consciousness, and to the dangers of taking it for granted. “I think (it) is one of the most precious things we have, and I think it’s under threat. In the same way that social media hacked our engagement and our attention, we’re now going to the next step – machines hacking our attachment, our deeper emotions. Helping people appreciate this gift they have will hopefully lead them to defend it.”

There’s a good chance he’ll succeed. “I feel very lucky and somewhat amazed that, in two very different areas, my books seem to have started conversations or helped launch them,” he reflects. I wonder which of the eight – including six bestsellers – people most often buttonhole him about. “Probably one of the food books, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, which is now 20 years old.” The sections on processed foods were ahead of their time, given the conversations people are having now, I point out. “People (still) want to know what to eat, and they’re very confused about eating,” he says. His next, short book – an Audible original, slated for 2027, will be about the microbiome – a contemporary obsession that he also lighted on early, having his own gut and skin bacteria genetically sequenced for an article back in 2013.

So do people stop him to talk about food more than their psychedelic experiences? “Oh, no, that happens all the time,” he says, with a you’ve-no-idea smirk. “I mean, I’ll be in a restaurant and someone will come up and start telling the story of their trip. Yeah, I’m the psychedelic confessor. And sometimes they’re interesting, but very often it’s like listening to someone talk about their dreams. Hard to take.”

Has he had any psychedelic experiences worth sharing recently? He smiles and then becomes a notch more solemn. “I did have one last year. It was not fun. It was very difficult, but very productive.”

How did he cope with it? “Fortunately, I was with somebody I trusted and was willing to deal with it, not fight it. One of the keys I’ve learned about psychedelic experiences: you need to surrender to them. And to the extent you resist what’s happening, you’re going to be very anxious and unhappy. What was interesting is that the experience also left me with all sorts of questions: it was very unresolved at the end,” he says. “And then I went to a meditation retreat two weeks later, and, without going into the details, the questions were answered in meditation.” There’s a genuine delight in his voice, a sort of glee at the discovery and an earnest desire to share, if not the contents, then the wonder of it. “I’ve always had a sense that psychedelic experience and meditation have very strong links, but I’d never seen it work quite like this,” he says, laughing and then shrugging contentedly: “another mystery of consciousness”.

A World Appears: A Journey Into Consciousness by Michael Pollan is published by Allen Lane. To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.